Setting up your company’s operating structure in Mexico

WEBINAR:

Setting up your company’s operating structure in Mexico

Who should attend this 1-hour webinar?

Executives whose companies face profitability or expansion challenges by manufacturing in the US, and who are considering Mexico as an alternative.

Why should you attend?

To hear the learnings of companies that located some or all their manufacturing to Mexico, from experienced advisors who will explain five typical structural approaches and their considerations.

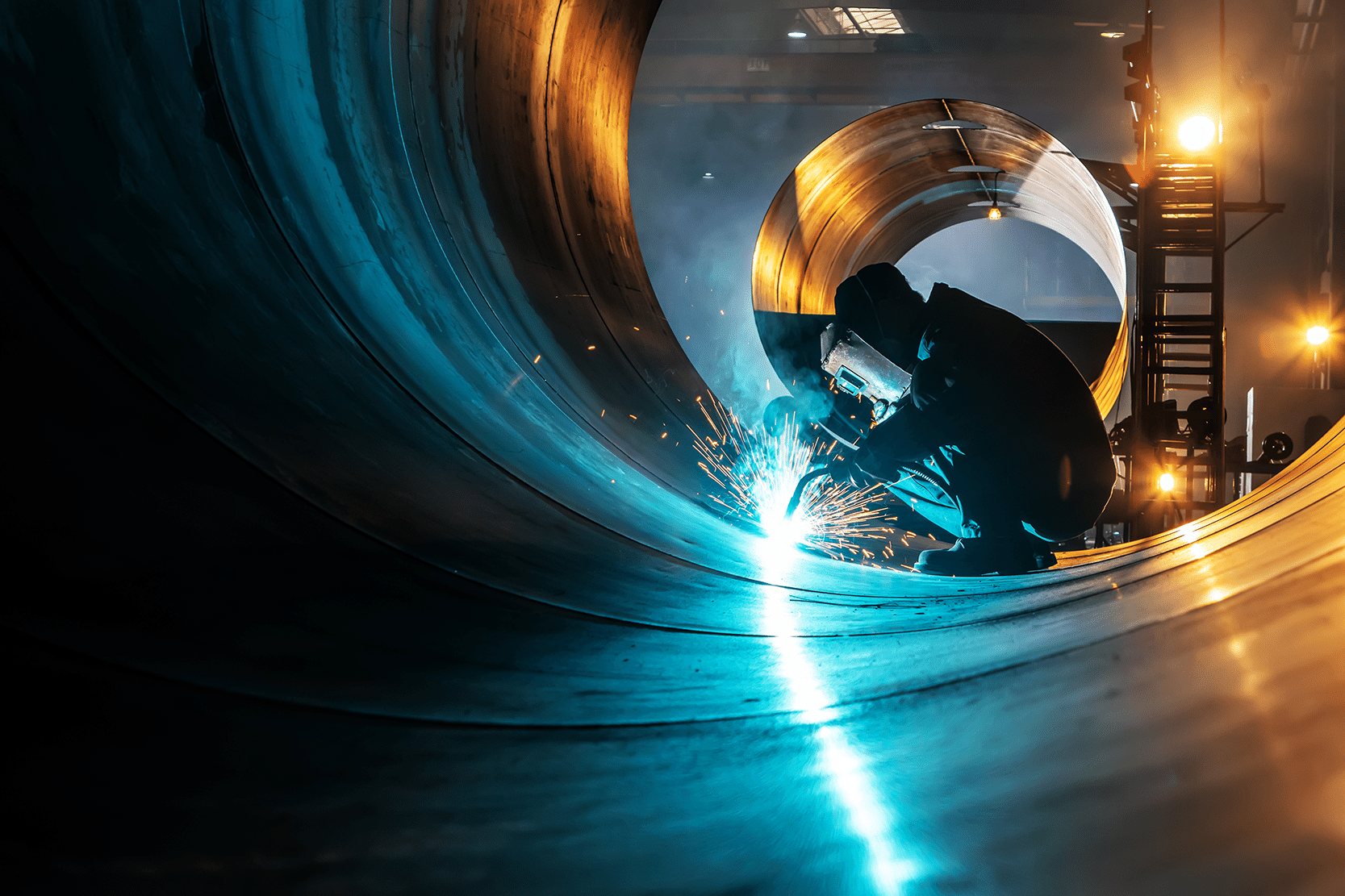

Increasingly, many companies – whose primary destination markets are in the US – are moving manufacturing operations or relocating specific links in their supply chain to Mexico.

Once you’ve decided to take advantage of the benefits of Mexico manufacturing, how should you structure your operation? Contract manufacturing? Assembly only? Your own factory (lease, buy, build)? A shelter service that provides space, people and back-office support for your factory?

EWA (East West Associates) advisors will present the pluses & minuses of structure options, including relative costs, how to minimize the costs, set-up time guidelines, and where in Mexico one should consider locating.

In this webinar, East West Associates speakers will share their first-hand knowledge of Mexico manufacturing options, and discuss how their US-based clients have incorporated Mexico in their manufacturing and sourcing operations.

Closing China Operations?

Speakers

This webinar features seasoned speakers with real-life experiences in closing over 70 China plant closures and relocations, and with sourcing both within China and within relocation target countries:

Dan McLeod, Director, East West Associates

Jacob Miller, East West Associates

Closing China Operations?

Watch Video

Closing China Operations?

Presentation

Timely Topics To Drive Growth.

Sign up for our webinars.

Sign Up